For long stretches during former President Donald Trump’s arraignment in Miami on Tuesday afternoon, the only sounds in the courtroom were the creaks of the wooden benches in the spectators’ gallery and the hum of the air-conditioning system. Trump, wearing a dark suit, sat between his two lawyers, Todd Blanche and Chris Kise. From time to time, he leaned to his right to whisper to Blanche. Blanche would cover his mouth as he replied, pressing his face into Trump’s shoulder, practically snuggling.

Every American should be afforded the opportunity to observe Trump sitting silently for an hour. As it was, a half-dozen members of the public and a few dozen representatives of the press had their names drawn out of a hat by the clerk of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida. In April, at Trump’s arraignment in Manhattan on thirty-four counts of falsifying business records, the former President said fewer than a dozen words. On Tuesday, facing federal charges—including willful retention of national-security defense information and conspiracy to obstruct justice—Trump said absolutely nothing. His lawyers did the talking for him. “Your honor, we most certainly enter a plea of not guilty,” Blanche said, a few minutes into the proceeding.

There had been speculation before the hearing that Trump wouldn’t be formally arraigned on Tuesday. Two of the lawyers who had been handling the case left his legal team last week, after the indictment against him was unsealed. Since the case will be tried in Florida, Trump needed a lawyer admitted to the bar in the state. But who would take such a case, with such a client, and at the last minute? Representing Trump right now means accepting a nonzero chance of ending up in legal trouble oneself. Federal prosecutors, led by the special counsel Jack Smith, built their indictment against Trump in part using notes kept by one of Trump’s own lawyers, M. Evan Corcoran, who will now likely be called as a witness in the case. But there was Kise, a veteran Florida lawyer with deep ties to the state Republican Party, sitting to Trump’s left. There always seems to be someone in a red hat or blue suit ready to step in for Trump, no matter the fate of the last guy.

Arraignments are usually considered perfunctory affairs, particularly in cases against wealthy defendants who can afford bond and stay out of pretrial detention. But nothing about the criminal prosecution of a former President is perfunctory. As was the case in April in Manhattan, Trump’s arraignment on Tuesday involved extensive discussion of Trump’s extraordinary circumstances. Prosecutors allege that Trump kept classified national-security documents in sloppily stored banker’s boxes at Mar-a-Lago, his private club in Palm Beach, and at his golf club in Bedminster, New Jersey, and that he engaged in a series of deceptions and scheming maneuvers when asked to return them. While discussing whether the judge presiding over the arraignment, Jonathan Goodman, would prohibit Trump from contacting witnesses in the case, Blanche argued that such a rule would be impossible for Trump to abide by, since the case involved so many elements of Trump’s life: his staff, his security detail, his clubs.

Trump’s co-defendant in the case is Waltine Nauta, a former White House military valet who has continued to work for Trump since the former President left office. The government says that Nauta was the other member of Trump’s conspiracy to keep the classified documents. Nauta was sitting at the defense table to Blanche’s right, his shiny bald head a contrast with Trump’s shiny blond head. Goodman said it was his understanding that Nauta was with Trump “on a daily or nearly daily basis.” Nauta’s presence meant that Trump had some familiar company in the courtroom. As was the case in Manhattan, no member of Trump’s family attended the hearing in Miami. There has been much talk about what kind of venue Florida will be for a Trump trial, and whether a jury here will be friendlier to the former President than one in New York. Calls had gone out for Trump supporters to protest the proceeding on Tuesday. But, for much of the morning, Trump fans were rivalled in number by the feral chickens that live on the grass outside the Wilkie D. Ferguson, Jr., Courthouse.

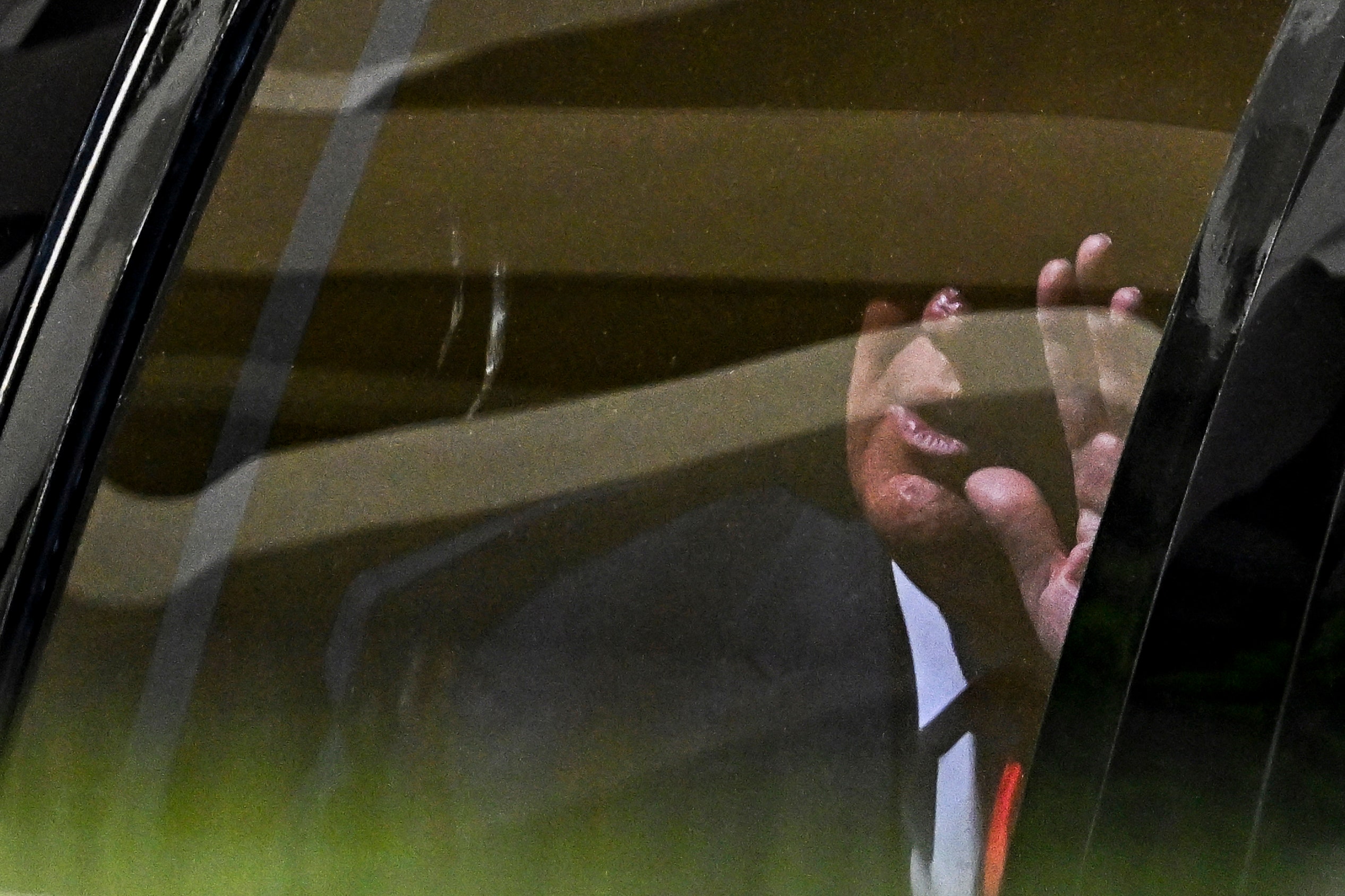

Eventually, the judge, the prosecutors, and Trump’s lawyers hashed out a plan wherein Trump agreed not to discuss the facts of the case directly with anyone whom prosecutors put on a list of potential witnesses. Otherwise, the prosecutors seemed to go out of their way to demonstrate that they did not want the case to restrict Trump in any way. He was not asked to surrender his passport. He was not asked to check in with pretrial services. He did not have to put up bail. Trump is running for President, after all. After about forty-five minutes, the hearing was over. Trump stood as the judge exited, and then he turned to look at the gallery for a moment before walking out through a side door. His head was set low on his shoulders. He was grimacing.

From the courthouse, Trump made what the Miami Herald called “strategic detour” to Versailles, a Cuban restaurant in Little Havana where his supporters had gathered. “Are you ready? Food for everyone!” he said, before a pastor and a rabbi who were on hand took a moment to pray for him. Then Trump headed for the airport, to fly to Bedminster, one of the scenes of the alleged crime, and the site of a fund-raiser he planned to attend in the evening. On Wednesday, Trump will be seventy-seven years old. He might end up President again, or he may face a terminal prison sentence. It remains impossible to say which is more likely. ♦